IEP Design and Definition

An Individual Education Program (IEP) is defined by Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) as “…a written statement for each child with a disability that is developed, reviewed, and revised in a meeting…” The regulation goes on to further clarify that first it must include:

- “A statement of the child’s present levels of academic achievement and functional performance…”

- measurable annual goals, including academic and functional goals…”

- “A description of…how the child’s progress toward meeting the annual goals… will be measured…”

- “A statement of the special education and related services and supplementary aids and services…”

- “An explanation of the extent, if any, to which the child will not participate with nondisabled children in the regular class and in the activities…”

- “A statement of any individual appropriate accommodations that are necessary to measure the academic achievement and functional performance of the child on State and district wide assessments [or alternative assessments]…”

- “Transition services. Beginning not later than the first IEP to be in effect when the child turns 16, or younger if determined appropriate by the IEP Team, and updated annually, thereafter…”

IEP Intent

The individualized education program (IEP) ultimately exists to assist students with disabilities, ages 3 to 21, in accessing public education, just as their similar aged peers would without specially designed instruction or accommodations and modifications to their curriculum.

In writing and implementing an IEP for a child’s disability, the Local Educational Authority (LEA) is providing the student equal access to the general education environment, to the greatest extent possible, in light of the student’s circumstances.

This equal access can be offered in many ways but often looks like specially designed instruction to address the student’s missing skills that are the result of an identified disability recognized by IDEA. As this is the case, the IEP process must take into account the student’s needs and provision a method to monitor the student’s progress.

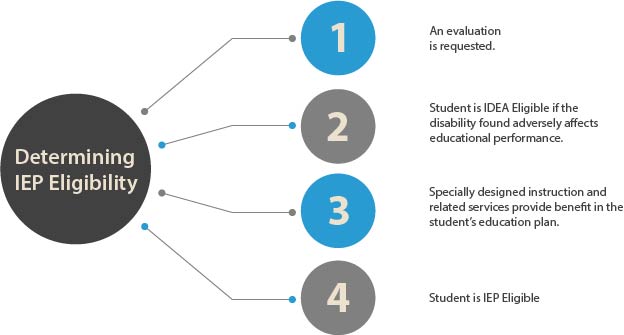

The IEP Starts with the Student in Mind

Before a special educator starts creating an IEP, they must understand the needs of each of their students. This starts with the evaluation. In a perfect world, the special education teacher will have spent time with the student through the evaluation process as an observer, at the very least, or better yet as a part of the multidisciplinary team by administering an academic achievement assessment such as the Woodcock-Johnson® IV.

Participating in this way gives an educator firsthand knowledge of the student’s needs; however, if this is not possible, the special educator should collaborate with the student’s general education teachers and the evaluation team. This will provide an opportunity to gain a more comprehensive understanding to write the child’s IEP.

While the evaluation often highlights the student’s needs, it can also provide insight into what the student does well. Student strengths are one of the most important things to understand regarding a student receiving special education services. Too often, parents have been informed about their child’s academic, social, or behavioral weaknesses, so it is crucial for the IEP to spotlight their strengths: or as my colleague would say “let them sparkle.” This is a great starting point for writing a student’s present level of performance.

While the strengths of the student are very important, the present level of performance begins in earnest with the area of eligibility and the child’s needs. The present level serves as a foundation for the entire IEP and guides the IEP team in providing appropriate IEP goals and services.

This initial statement regarding the child’s disability is an integral part of the IEP, as it helps to guide the IEP team members to make decisions regarding specific goals and how to provide services in the least restrictive environment (LRE).

Beyond this, the present levels of performance focus on the student and their access to and progress in the general education curriculum.

The Present Level of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance

As mentioned above, the present level of performance provides a foundation for the entire individualized education plan. The present level also helps focus the IEP meeting on the student’s areas of need, which in turn helps develop appropriate IEP goals and benchmarks. Furthermore, defining a child’s disability helps to establish a need for services to include related services. More specific details regarding the various sections are as follows.

How the Child’s Disability Affects Their Involvement and Progress in the General Education Curriculum

The various sections of the present level of performance, including this initial statement, serve as a report from the school district to the parent of how their child’s disability impedes their access to the general education curriculum. Most of the statements contained in this part of the IEP are data driven and district generated; however, the strengths of the child and the concerns of the parent/guardian sections allow the family members an opportunity to have a voice as an IEP team member.

Using the information from the last evaluation, the child’s disability is explained and states how it affects their access to and progress in the general education curriculum. It should be clear from the first sentence what the child’s specific disability is, (i.e., specific learning disability in the area of basic reading skills). The statement should focus on why a student requires specially designed instruction, why general education interventions are not enough, and the use of data from the most recent evaluation to justify these claims. Ultimately, this statement is used to develop IEP goals and services that come later in the IEP document. It should also state that special education services are necessary to make progress toward grade level expectations. It is helpful to explain why general education interventions were not enough to allow them to participate fully in the general education curriculum. All of these statements help reinforce other written statements throughout the IEP.

Strengths of the Child

As mentioned above, the strengths of the child may be identified through evaluative measures, but also may require collaborating with various IEP team members that work with the student daily.

Do not identify superficial strengths in this section, but really dig down for social, academic, and behavior strengths; this is especially true when considering the student and their circumstances.

Parents may also have insight regarding their students’ strengths that may not be evident in the school environment. The district should make note of these and document the parent’s perspective.

As a rule, try to make this part of the IEP as robust as possible. The inherent nature of the IEP is to focus on student weakness to provide appropriate services, but this is an opportunity to focus on the best the student has to offer.

Concerns of the Parent for Enhancing the Education of the Student

This part of the IEP may well be the most important. This section allows parents/guardians to truly have a voice in the IEP process. While a meeting may start with the present level, it may be more appropriate to come back to this section at the end of the meeting. This allows the school district to present the IEP in its entirety and answer questions presented by the family members.

After all is presented, it is likely the parents/guardians will have a concern; make sure to document it within this section and note how the school district intends to respond. The response may be a prior written notice; however, it could be an added service or additional minutes of specially designed instruction.

Changes in Current Functioning Since the Initial or Prior IEP

This section provides the special education teacher an opportunity to celebrate the progress made throughout the IEP year. This is becoming more important since the Endrew F. Supreme Court Decision. Expect that state agencies will shift their gaze from simple compliance to analyzing progress reports and progress monitoring.

When writing an initial IEP, this section should not be left blank. Consider writing something like “June was evaluated on 12/15/2022 and found eligible for special education services. This is her initial IEP; in following years this section will detail her growth or the discovery of new challenges.”

As the annual IEP comes due, consider the growth of the student. Use this part of the IEP to explain the growth and the path forward for the student to make progress toward accessing the general education curriculum. Furthermore, it may be appropriate to include state and district assessment results to explain how the student is able to engage with the curriculum. This part of the IEP may also provide an opportunity to highlight a new challenge for the student as well.

Summary of Evaluation Results

Always consider the most recent evaluation when writing this part of the IEP. The summary of the evaluation results provides a snapshot of why the student met initial or continued eligibility. Using the synthesis of the evaluation results will be adequate to complete this section of the present level. It does not need to include every detail about each assessment given; however, it should include the scores of the assessment and how they were used to establish eligibility. This information will remain constant until the student has a reevaluation. Simply put, this information is helpful to whomever reads it, as it helps to explain how the student was identified for special education services.

Formal and Informal Transition Assessments

This section of the present level provides a path for the student’s future. It explains how the school district will assess the student to develop post secondary employment or education goals to assist in transition planning. This section is most prevalent when the student enters high school and is required when the student will turn 16 years of age during the IEP cycle (so when a student is 15 years old). Should the student be younger, do not just write “N/A,” provide a short explanation that states that this section is not applicable due to the student’s current age, but should the student continue to require special education services at age 15, the school district will assess the student to determine appropriate post secondary transition goals.

Alternative State Assessments

There are times when the standardized state assessments will not adequately assess a student, due to the nature and severity of their disability. This area indicates that a student is taking an alternate assessment. Alternative assessments are designed for students who are identified as having the most significant cognitive impairments. IDEA requires states to develop specific qualifications for alternative assessments. As a result, special educators should refer to their state level department of education for criteria. The state criteria will have specific verbiage to use when writing a justification for alternative assessments.

Special Considerations

The IEP is designed to provide as much information as possible about the child’s disability. The special consideration page is a simple and effective way to do this. This section of the IEP covers things like: sensory deficits (specifically hearing and visual impairments), behavioral concerns, limited English proficiency, communication delays, assistive technology needs, extended school year (ESY) participation, state and district assessments, post secondary transition services, and alternate means of instruction (AMI). While most of these may not apply or involve a simple answer, there are two that require greater detail and will be addressed below.

Behaviors That Impede Learning

The special considerations page asks questions about the student’s condition to include this: “Does the student exhibit behaviors that impede his/her learning or that of others?” If the answer is yes, it requires additional information on how the school district intends to mitigate these behaviors. It may be as simple as the student’s behavior being addressed through general education behavioral interventions. It is often the case that a student’s behavior has been assessed using a functional behavior assessment, and the behaviors are addressed in the IEP through a Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP). If this is the case, a statement should be written explaining the inclusion of the behavior plan in the IEP and that the identified behaviors are linked, or not linked, to the child’s eligibility area. Being detailed in this section may be key to protecting both the student and district in the event of a manifestation determination or due process complaint.

Assistive Technology

The second area of the special consideration’s page that requires greater detail is the Assistive Technology (AT) question. If the answer is yes, the student requires assistive technology, then the statement should include a justification of why and the types of assistive technology a student will use.

Extended School Year

Not every student with an IEP requires extended school year (ESY). The IEP must consider data to determine the need for ESY. This data should be relevant to the IEP goals, and it must show significant regression of skills over an extended break in education. The caveat is that the regression must be so significant that the student could not recoup the skill in a reasonable amount of time. One other note, it is possible that the nature and severity of the child’s disability warrants ESY services to continue making progress on their IEP goals. If the annual IEP meeting is held during the first semester, it may be appropriate to revisit the decision for ESY in March or April.

IEP Goals and Objectives

Goals are what differentiates an IEP from other programs designed to help students with disabilities. In an IEP, each goal can be tied back to specific statements in the present level. Each service provider must carefully write their goals to be specific, measurable, attainable/ambitious, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Endrew F. vs. Douglas County also provided new guidance related to IEP goal development and data collection. In the linked fact sheet (above) from the US Department of Education, Question 13 doubles down on the need for ambitious goals to help the student be “involved in, and make progress, in the general education curriculum.” It is also noted in that section that state curriculum standards are a guide and not a replacement for IEP goals.

When creating goals for students who participate in Alternative State Assessments, short-term objectives must be included. These objectives may be tied to steps related to independent living skills or social skills. Including objectives serves two purposes, they help provide the student a road map of how they will attain the goal and highlight additional skills that can be assessed using whatever measure is used by the state.

The Endrew F. decision also increased the standard for data collection and progress monitoring. Luckily, technology has helped school districts increase their ability to do this simply. Web applications like SpedTrack, have built-in solutions to allow special educators easy access to collect and analyze data. Given a baseline and subsequent data points, SpedTrack’s software will calculate trend lines allowing the IEP team to see a child’s progress. SpedTrack will also provide a printed graph to accompany quarterly progress reports that can be sent home at the same time as report cards.

Transportation

Where it is appropriate, Transportation can be added to an IEP as a related service. The team must consider the following: If the district does not provide transportation, will the student be able to access their special education services? The answer to this question may be yes, and if so, the student is likely able to ride a bus independently or has parent/guardian provided transportation. If the answer is no, it may be due to the severity of a student’s disability or their bus riding behavior. The team must make this decision, but it should not be provided just as a convenience for the parent.

The Service Summary

The service summary page outlines the total number of minutes a student will be served though the IEP. The services selected should correspond to the individual goals that were written and, to a greater extent, be directly tied to statements within the present level of performance. When selecting service minutes, the team must always consider the LRE, as the goal is always to make progress on the IEP goals while allowing the student to participate in the general education environment to the greatest extent their circumstances allow. Service minutes include specially designed instruction, related services, supplementary aids and supports, as well as Parent and Teacher supports.

Educational Placement and Participation

The educational placement of a child with a disability is directly tied to the number of minutes a student receives outside of their general education classes. There are many placement codes, but the most common are, within the general education environment 80% or more, within the general education environment 40% – 79% of the time, or within the general education environment less than 40% of the time. Again, technology has helped us with this calculation and as long as you know the weekly total of minutes for a school, programs like SpedTrack will provide the amount of time in and out of the classroom.

Along with this percentage, the case manager must provide a statement of justification about why the student requires specially designed instruction outside of their general education classes. This often comes down to the nature and severity of the child’s disability; however, the statement must be specific to the student and their needs.

Accommodations and Modifications

Accommodations and modifications are strategies that are implemented in general education classes and are not classified as a means of differentiation within that environment. These accommodations and modifications are used in the classroom and in the administration of district and state assessments. Since these accommodations and modifications are often implemented in the general education classroom, it is important to have buy-in from all the student’s teachers. Additionally, it is a good idea to have the general educator present these to the family members during the IEP meeting in an effort to reinforce inclusion. Furthermore, these accommodations and modifications may address additional comorbid conditions such as ADHD, even when a student is identified in a different category. These conditions should be noted in the present level to better explain why these strategies are in place.

IEP Writing Conclusion

This blog was designed to provide a detailed step by step overview to special education professionals who write IEPs. While every area of the IEP was not covered in depth, it’s hoped that this overview has provided unique information to inspire a student-centered IEP that is inclusive, tailor-made to their needs, and expertly written.